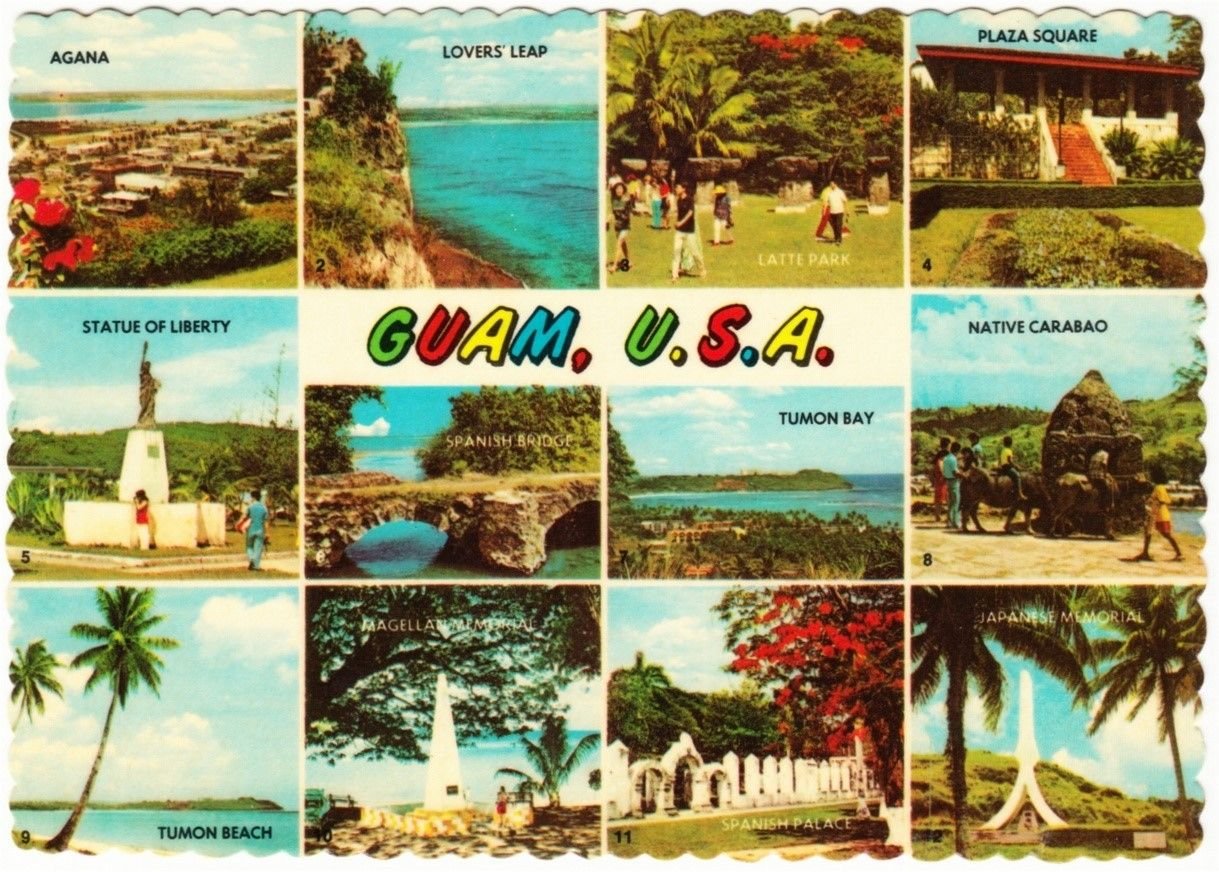

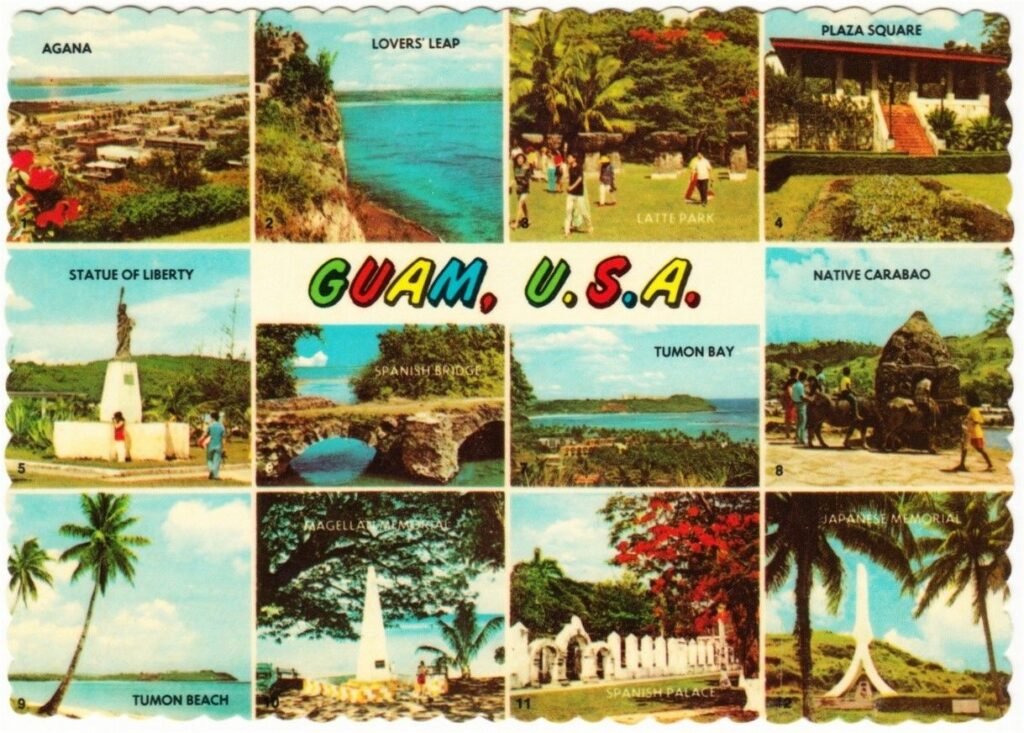

On a map, Guam is a speck, a comma in the Pacific sentence. For decades, though, it carried the improbable weight of a destination that promised forever: honeymoons that outshone Hawaii, shopping sprees gilded by tax-free indulgence, and beaches that seemed to bend toward the sky in a perpetual invitation. It was, for a time, enough.

But islands, like industries, are fragile organisms. One generation’s miracle is the next generation’s nostalgia. Today, Guam finds itself caught between the faded memory of its heyday and the anxious anticipation of what might come next. The tourists have not disappeared, but they have changed—more Korean than Japanese, more restless than loyal, more demanding of experiences that are not simply sand and salt water.

To make sense of this uneasy moment, I spent an afternoon listening to George Takagi, a man who has, improbably, lived several versions of Guam’s economy: first as a tomato farmer in the late 1960s, then as an insurance broker, and now as a reluctant philosopher of the island’s tourism woes. His story is less biography than parable, and his warnings—about typhoons, about insects, about the loss of birdsong—carry the ring of lessons learned too late.

What Beauty Means When the Birds Are Gone

Takagi’s reflections return, again and again, to the land itself. Once, Guam had birds; then the snakes came, and the silence fell. Once, it had flowers; now, the petals are fewer, the colors dimmer, the scents easily overlooked. “We can’t sell just the beach anymore,” he told me. “Every island has a beach. What do we offer that is different?”

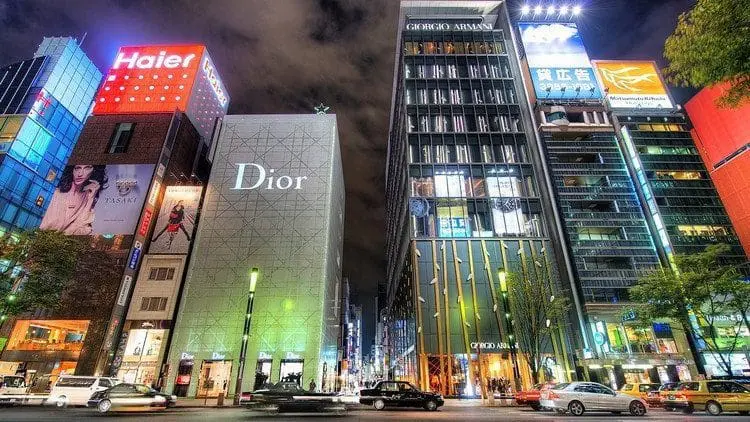

It is not a question of marketing so much as a question of meaning. Tourists can buy a Louis Vuitton bag anywhere now—Tokyo’s boutiques are cheaper, even with the tax. The honeymooners who once made Guam their paradise now drift elsewhere. What remains, then, is the possibility of cultivating something more elusive: the experience of beauty that feels unmanufactured, the kind that makes travelers pause and imagine staying longer, or perhaps returning.

This is, in its way, a radical idea—not building higher hotels or brighter malls, but restoring birds and planting flowers. Rewilding as a tourism strategy.

The Problem of Smallness

Every island knows the temptation of smallness: to guard its own, to compete with its neighbors, to believe its fortunes rise and fall alone. Takagi refuses that logic. “Don’t think only about Guam,” he said. “Think about other islands and working together.” His vision is of a Southern Pacific archipelago united, offering a lattice of experiences that wealthy travelers can drift among: Guam for beaches, Palau for reefs, Yap for culture, Saipan for its echoes of history. Not competition, but a choreography.

It is, of course, easier said than done. Collaboration requires a generosity that economies rarely afford. Yet his insistence lingers: an island that thinks too small condemns itself to smallness.

Who Gets to Stay

Perhaps his sharpest critique is not of typhoons or taxes, but of the advice given to Guam’s young. Too often, he hears business leaders tell students to leave—go to the mainland, learn, return later if you wish. But by then, Takagi warns, they have lost what tethered them to Guam in the first place. “If you leave, you lose what makes you special to Guam,” he said. “You make Guam into the States.”

He imagines instead a different trajectory: one where young people are not underpaid adjuncts to a global industry but central to its reinvention. They speak English, they understand the island’s rhythm, they know its contradictions. Why import expensive talent from Tokyo or Seoul, he asks, when the island’s own graduates could carry the future?

It is a question less about economics than about dignity, and about the possibility of building a future that feels like home.

Toward Tomorrow

The future of Guam’s tourism will not be found in another duty-free catalog. Nor, perhaps, in another advertising campaign of turquoise waters and golden sand. It lies, if Takagi is right, in something subtler and harder to measure: in the restoration of natural beauty, in the willingness to think beyond Guam’s shores, in the courage to trust its young people.

Is this dream naïve? Perhaps. But it is no more naïve than the idea that a tiny island could once reinvent itself as the “honeymoon capital” of Japan. Islands, after all, live on reinvention. The question is whether Guam will have the patience—and the imagination—to do it again.

Author’s Note: This article is shaped by an extended interview with Hidenobu “George” Takagi, conducted for academic research on Guam’s tourism industry. His reflections are presented here as a lens through which to consider the island’s precarious future.